Eight Illusions That Will Show That You Can't Trust Your Senses At All

The Oxford Dictionary defines a sense as “a faculty by which the body perceives an external stimulus.” Most people can name five – sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch – but some scientists reckon we could have as many as 33, including equilibrioception (the sense of balance) and nociception (the sense to feel pain). In the not-too-distant future, humankind may be able to add even more to the list thanks to rapid advances in technology.

However, if you think you can trust your senses, you are sadly mistaken. Here are eight illusions that prove exactly that.

White’s Illusion

An optical trick known as “White’s Illusion” was developed by an Australian psychologist called Dr Michael White after he spotted an unusual design by an 11th-grade student in a book on optical art. The illusion involves just three shades: black, white, and gray. Yet, most people see four. This is because of the way the gray is embedded into the black and white stripes, which makes it look as though there are in fact two shades of gray.

It’s not known what causes this phenomenon, but several researchers have put it down to a concept called the belongingness theory. Essentially, our perception of the gray blocks is shaped by the color of the lines surrounding it, so when it is embedded in black lines, it appears darker and when it is surrounded by white lines, it looks lighter. The exact same thing happens when color is added to the mix.

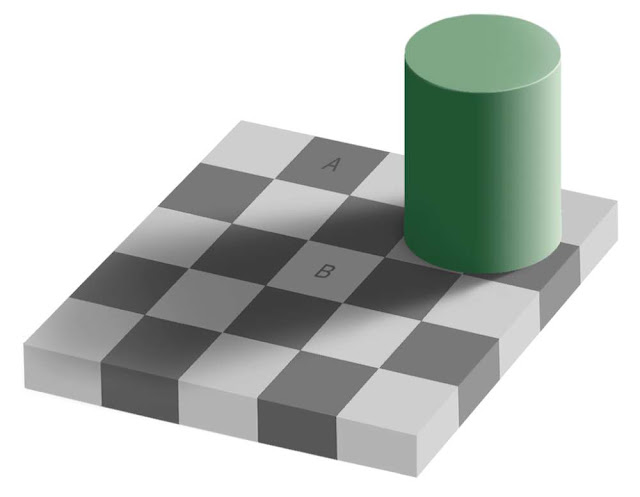

We also see something similar with Edward H. Adelson's checker shadow illusion.

Believe it or not, tile A is the same color as tile B. Yet, our brain "adjusts" the color to compensate for the perceived shadow.

Still don't believe us?

Want to see another color mind-blow like #TheDress happen in real-time? http://t.co/tsb5Otkoa9 pic.twitter.com/YHRI4e1SWc— Kyle Hill (@Sci_Phile) February 27, 2015

Troxler’s effect

Every day, we are bombarded with a constant stream of stimuli. It's distracting – so, to compensate, our brain blocks out anything our subconscious decides is unnecessary. This is why you can't smell your own perfume and rarely notice the feel of your clothes on your skin.

It also explains a sensation called "Troxler's Effect", invented by Ignaz Troxler, a physician and philosopher, way back in 1804.

If you stare at the center of the image for 30 seconds or more, you will notice the details on the periphery simply fade away. This is because your brain blocks them out, thinking they are unnecessary, and, instead, "fills in" the space with the white background.

Take a quick detour to Google and you will find various different images that produce the same result. It may also be the same phenomenon behind the Bloody Mary folklore.

The Ebbinghaus Illusion (or the Titchener Circles)

Look at the two center circles. Which is bigger?

You probably know this is a trick question and you'd be right. The two circles are the same size, but most people perceive the circle on the right as bigger than the circle on the left. This is because we subconsciously use context to assess how big or small a particular object is – a process called the "Ebbinghaus Illusion". Therefore, we see the circle surrounded by smaller circles as bigger than it really is and the circle surrounded by larger circles as smaller than it really is.

A 2008 study discovered that pigeons were equally dumbfounded by this particular trick – only that they saw the center circle surrounded by larger circles as bigger than it really was and the center circle surrounded by smaller circles as smaller.

McGurk Effect

The "McGurk Effect", named after Harry McGurk, is a visual-auditory trick that uses sight to dupe our hearing. Watch the video below and you will most likely hear the man in the video repeat the word "bah" over and over again. But partway through, his mouth movements change and, instead of "bah", most people will "hear" the word "fah".

Guess what? He was saying the word "bah" the whole time.

This illusion reveals just how much we rely on our sight when it comes to hearing. The self-deception occurs because there is a conflict between the visual speech patterns and the noise he makes, and so our brain responds by fixing the sound to match the lip movements.

It seems most of us trust our eyes over our ears, but that is not so for musicians. A 2016 study found that skilled musicians were immune to the phenomenon.

Shepard Tone Illusion

An audio trick called the "Shepard Tone Illusion" manipulates the brain into thinking the tune continues to ascend in pitch. In reality, it is a musical clip that loops over and over and over, never rising in pitch – as Vox describes it, it is the audio equivalent of a barber's pole.

This works because there are three layers of sound layered on top of one another. The highest pitched layer becomes quieter as the clip goes on, while the lower pitch gets louder and the middle pitch remains constant. Even though the clip is repeating itself and, therefore, isn't actually getting any higher, the listener hears two tones rising in pitch and believes the tune is constantly escalating. The result: a tense, emotional sound – an effect Hans Zimmer frequently employs in his musical scores.

Tritone Paradox

In 1986, Diana Deutsch came up with the "Tritone Paradox", a variation on the "Shepard Tone Illusion". Two tones separated by a tritone or half-octave are played over and over. Some people will "hear" the tune ascending in pitch, whereas others will "hear" it descending.

Both sets of people are wrong because, in reality, it is the same two tones repeating. However, the side of the fence you fall on could say something about your upbringing. Studies have shown that the way the two tones are perceived varies according to a listener's language and dialect. People from Vietnam, for example, will hear the tones differently to people from California. Other studies suggest that even your parent's upbringing can have an influence.

The Rubber Hand Illusion

Phantom limb syndrome affects many people who have had an arm or leg amputated, but even non-amputees can be deluded into thinking they have an invisible hand.

To perform this trick, sit at a table with a screen running through the middle and keep your right hand hidden while holding your left hand out in front of you. Next to your left hand, introduce a rubber hand. If both your left hand and the right hand are stroked simultaneously, your mind might "feel" the sensation on the rubber hand.

The Illusion of Taste.

This one is going to require some props, specifically two glasses of white wine and some red food dye.

You might think you can tell your red from your white with your eyes closed, but a 2001 study involving 54 enology students suggests otherwise. The volunteers were asked to describe the flavor notes of two glasses of wine, one white and one red. Words like "honey", "lemon", "lychee", and "straw" were used to describe the glass of white, whereas words like "prune", "chocolate", and "tobacco" were used to describe the glass of red.

The twist: They were describing the same bottle of wine. The researchers had dyed the naturally white wine red in one glass.

If you are not a big wine drinker, you might want to try a similar experiment with chip packets. Charles Spence from Oxford University duped tasters into confusing salt and vinegar chips with cheese and onion chips. He told The Guardian that "many of our subjects will taste the color of the crisp packet, not the crisp itself."

No comments